November 22, 2022

If you’re fortunate enough to be in this situation, selling your home could trigger a sizable gain that could exceed the federal home sale gain exclusion of $250,000 ($500,000 for married couples who file joint returns). Then, the big gain triggers an unfortunate tax result: a federal income tax bill (and possibly a substantial state income tax bill, too, depending on where you live). Here’s an idea to consider to help you avoid this outcome.

Double Tax Savings

One strategy is to combine the principal residence gain exclusion break with the tax-deferral advantage of a Section 1031 like-kind exchange. With proper planning, you can accomplish this tax-saving double play with IRS approval.

The double play is available to homeowners who can arrange property exchanges that satisfy the requirements for both breaks. The kicker is that tax-deferred Sec. 1031 exchange treatment is allowed only when both the relinquished property (what you give up in the exchange) and the replacement property (what you acquire in the exchange) are used for business or investment purposes.

That means you must show that you have converted your former principal residence into property held for productive use in a business or for investment before making the exchange. According to IRS guidance, it generally takes a minimum of two years of business or investment use to qualify for this favorable tax treatment.

Gain from Relinquished Property

According to the IRS, the principal residence gain exclusion rules must be applied before the Sec. 1031 exchange rules when you’re able to combine both breaks. In applying the Sec. 1031 rules, you can potentially be taxed when you receive “boot,” which means cash or property other than real estate received in exchange for your relinquished former personal residence.

However, boot is taken into account only to the extent that it exceeds the gain that you can exclude under the principal residence gain exclusion rules.

Basis in Replacement Property

In determining your tax basis in the replacement property (that is, the new property you receive in exchange for your old home), any gain that you exclude under the principal residence gain exclusion rules is added to the basis of the replacement property. Any cash boot that you receive is subtracted from your basis in the replacement property.

The gain that’s deferred under the Sec. 1031 exchange rules is also effectively subtracted from your basis in the replacement property. But that’s OK, because you’ve successfully deferred what would have been a taxable gain upon the disposition of your former personal residence. (See “How the Double Play Works” below.)

Conversion to Rental Property

To cash in on the combination of the principal residence gain exclusion and Sec. 1031 exchange breaks, you must convert your highly appreciated principal residence into a rental property before swapping it in a Sec. 1031 exchange. Without explicitly saying so, IRS guidance apparently established a two-year safe-harbor rental period rule. A shorter rental period might work, but it could be challenged by the IRS.

Important: To take advantage of the principal residence gain exclusion break, your former principal residence can’t be rented out for more than three years after you vacate the premises. That’s because you must have used the place as your principal residence for at least two years during the five-year period ending on the exchange date. So at least two years of renting is good for purposes of converting your former residence into a rental property in order to accomplish a Sec. 1031 exchange. But three years of renting is too long if you also want to benefit from the principal residence gain exclusion break.

How the Double Play Works

Here’s a hypothetical example to show how you can double your tax savings by combining the home sale gain exclusion with a Section 1031 like-kind exchange. Jack and Jill have owned a principal residence for many years, and it’s now worth $3.3 million. After discussing the situation with their tax advisor, the couple decides to convert the home into a rental property. After renting it out for two years, they’ll exchange it for a small apartment building worth $3 million plus $300,000 of cash boot (paid to the couple to equalize the values in the exchange).

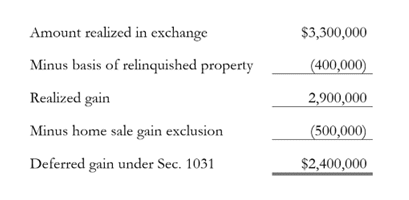

Their basis in the former personal residence at the time of the exchange is just $400,000. So, they realize a $2.9 million gain on the exchange. That’s calculated by subtracting the basis in the relinquished property of $400,000 from the sales proceeds of $3.3 million (apartment building worth $3 million plus $300,000 in cash).

IRS guidance stipulates that Jack and Jill must first apply the principal residence gain exclusion rules to exclude $500,000 of the $2.9 million gain. So, on their joint federal income tax return for the year of the exchange, the couple would exclude $500,000 of the $2.9 million gain under the principal residence gain exclusion rules. That leaves a remaining gain of $2.4 million.

The relinquished property is investment property at the time of the exchange (due to the two-year rental period before the exchange). So, the Sec. 1031 exchange rules may be applied. Under those rules, Jack and Jill are not required to recognize any taxable gain, because the $300,000 of cash boot they receive is taken into account for this purpose only to the extent it exceeds the gain excluded under the principal residence gain exclusion rules. Because the $300,000 of boot received is less than the $500,000 excluded gain, Jack and Jill have no taxable gain from the boot. That means, under the Sec. 1031 rules, Jack and Jill can defer the entire remaining gain of $2.4 million.

Here’s a summary of how the double play worked in this scenario:

What is Jack and Jill’s basis in the replacement (apartment building) property? Their basis is $600,000 ($400,000 basis of relinquished former principal residence plus $500,000 gain excluded under principal residence gain exclusion rules minus $300,000 of cash boot received). Put another way, their basis in the apartment building equals its fair market value of $3 million at the time of the exchange minus the $2.4 million gain that was deferred under the Sec. 1031 like-kind exchange rules.

Important: If Jack and Jill own the apartment building until they die, the deferred gain will be eliminated thanks to the date-of-death basis step-up rule. Under that rule, the federal income tax basis of the building is “stepped up” to its fair market value as of the date of death. So, their heirs could sell the building shortly after they die and owe little or nothing to Uncle Sam. The heirs would owe tax only on any post-death appreciation.

Right for You?

Under the right circumstances, combining the principal residence gain exclusion break with the tax-deferred Sec. 1031 exchange break can result in major tax savings. If you think this double play might work for you, consult your tax advisor. It takes time to successfully execute this tax-saving strategy, or reach out to us at the contact info below.

Senior Manager, Tax

Email

Troy Turner, CPA

Vice President and Director of Tax

Email

© 2022